If you believe (as I do), that the government bought spyware, then here are some pertinent questions

Question 1: Do these government agencies actually have investigative powers?

While the police might have the legal authority to investigate someone, does the PMO, MACC or anyone else share that authority. If a government agency has no right to investigate someone, then why is it buying spyware?

The conversation should end here, as I don’t believe the PMO has any authority to use spyware, but the next question actually goes even further and ask if anyone has the legal authority to use it.

Question 2: Is spyware legal?

Installing spyware on a laptop or smartphone is far more intrusive than a regular home search, it’s like having an invisible officer stationed in your house listening in on everything you say and do. It doesn’t just invade the privacy of the victim, but even those that victim communicates with, shares their laptop with or even those that just happen to be nearby.

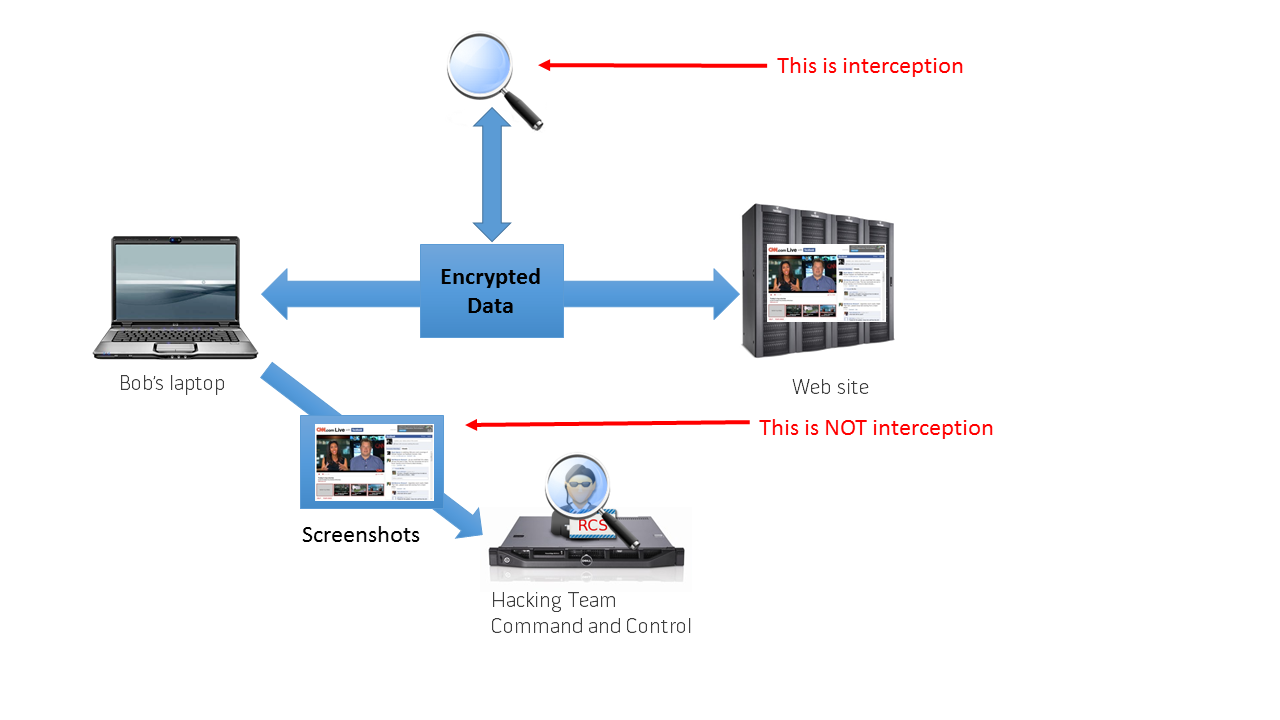

The MACC act, that governs the powers of the commission, specifically state that a the Public Prosecutor or Commissioner of the MACC can authorize the interception of communications if they ‘consider’ that the specific communication might help in an ongoing investigation. However, spyware from hacking team isn’t really ‘intercepting’ communications, because what is being communicated through the Internet is usually encrypted, Hacking team circumvents this by capturing the data before it is encrypted and then sends that captured data in a separate communication back to its control servers. Strictly speaking, this isn’t interception, its shoulder surfing on steroids.

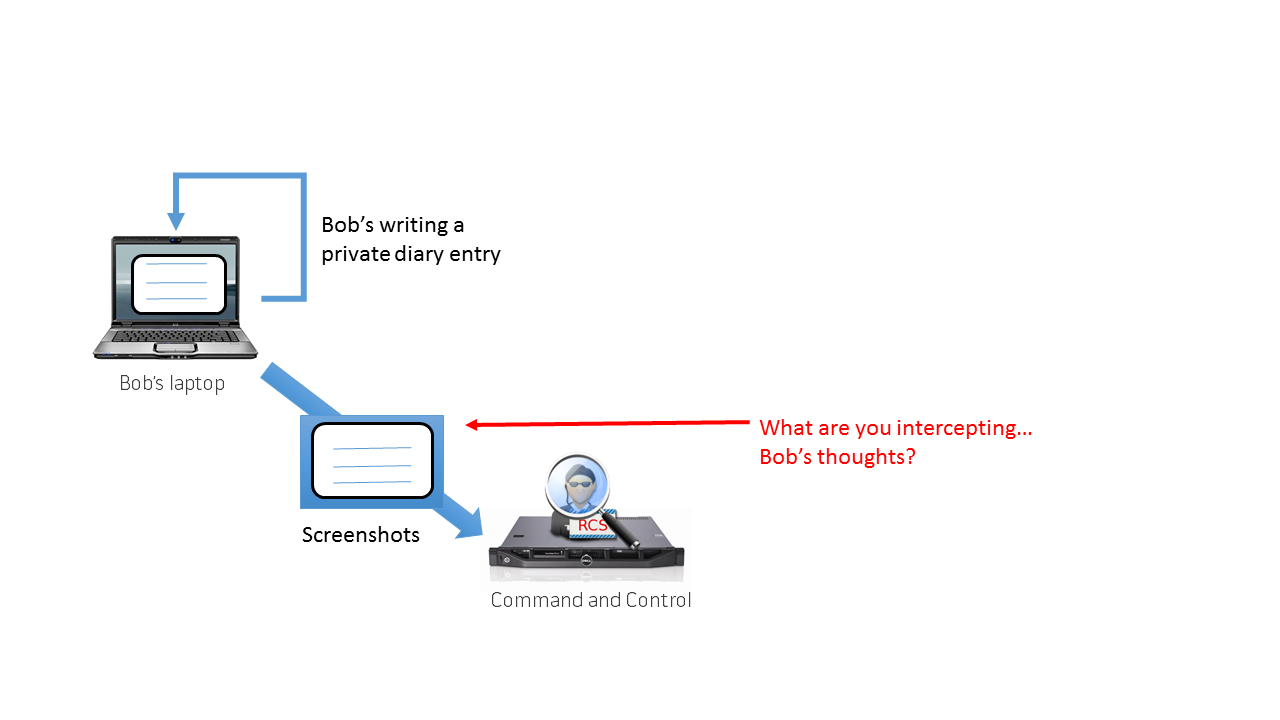

More worrying, is that the spyware might take screen shots of diary entries and notes that the victim never intended to communicate with anyone, or draft e-mail entries that they later delete are also captured by this spyware. Obviously this falls into a different category than simple ‘interception’, but I’m not done yet.

More worrying, is that the spyware might take screen shots of diary entries and notes that the victim never intended to communicate with anyone, or draft e-mail entries that they later delete are also captured by this spyware. Obviously this falls into a different category than simple ‘interception’, but I’m not done yet.

Hacking Team proudly proclaim that their software can remotely trigger the webcams and microphones on laptops to begin recording, essentially placing a spy at the homes of their victims to listen in on private conversations that were never intended for anyone outside the home. It may also violate the privacy of the household that the infected smartphone or laptop happens to be in, and could be used to determine far more intimate details of innocent bystanders including “the hour each night the lady of the house takes her daily sauna and bath”, far exceeding what is reasonably needed for a criminal investigation.

The legislation in Malaysia permits the use of searches of private property as well as communication interception, but clearly makes a distinction between the two as they represent different levels of privacy intrusion. In America you need a warrant to go into someone’s home, but a super-warrant for wiretap. I would suggest that nothing in our law allows for the installation of such nefarious spyware, and the use of the spyware is illegal regardless of whether the government agency has investigative powers.

Question 3: What was the purpose of these programs

Now, if we establish that indeed it is legally possible for the PMO to run a surveillance program, we then have to ask what was the purpose of the program. The public might be sympathetic to a Government agency investigating ISIS or other terrorist organizations. But the PMO doesn’t go after terrorist, and from all the evidence it seems they used it for political purposes.

Even the MACC need to show us which criminal investigations were helped by the use of spyware, (if any).

Question 4: Is it right to have a 3rd-party operate the spyware?

In all the cases, the operations of the spyware was done by a 3rd-party company called Miliserv. Now, the Police have investigative powers–but they can’t outsource that surveillance to a 3rd-party. The IGP can’t wake up one morning and outsource all Police investigations to his brothers company, but that’s exactly what the MACC did by outsourcing their investigations to Miliserv.

Remember the invisible officer I mentioned, imagine if that officer were a 3rd-party contractor to a incompetent software vendor rather than an officer of the law….creepy!

Question 5: Why did the Government try to cover up buying spyware?

The real smoking gun is why the Government tried to hide its tracks.

Not only did the PMO ask for the spyware it imported to be wrongly declared in customs declarations, but even on a technical level Hacking employed ‘anonymizers’. All spyware has to report back to a central server, and by right that server has to be located in country–for local government access. BUT, Hacking Team provided a ‘feature’ that routed the information across the globe first to obfuscate the source of the spying.

So if the Government installed spyware on your machine–it would first send detailed information about you to a server in the US, and then the UK, before finally ending up in Malaysia to obfuscate the fact that the government was spying on you. Even if you found out, you’d only know that you were being spied upon by an American server.

What this means though is that your personal information is zipping around the world, and more importantly even the Government knows it needs to hide it’s tracks. Why the need for such obfuscation if the government was acting Legally.

Conclusion

It’s really important we get to the bottom of these questions especially question 2, as these are not just gross invasions of privacy and over-stepping of legal boundaries, it sets the scene for future government transparency. If the government can get away with this, it will continue to doing it, if we want a better government we need to hold Ministers who lie in Parliament accountable, and hold office-bearers accountable for when they exceed the law.

It’s important, because if Malaysians don’t hold our Government up to high standards, they will inevitably end up having no standards…

Post-Script

As a final bit, here is what the Malaysian Criminal Procedure code states:

“Notwithstanding the provisions of any other written law, the Public Prosecutor or an officer of the Commission of the rank of Commissioner or above as authorized by the Public Prosecutor, if he considers that it is likely to contain any information which is relevant for the purpose of any investigation into an offence under this Act, may, on the application of an officer of the Commission of the rank of Superintendent or above, authorize any officer of the Commission—

(a) to intercept, detain and open any postal article in the course of transmission by post;Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission

(b) to intercept any message transmitted or received by any telecommunication; or

(c) to intercept, listen to and record any conversation by any telecommunication, and listen to the recording of the intercepted conversation.

(2) When any person is charged with an offence under this Act, any information obtained by an officer of the Commission in pursuance of subsection (1), whether before or after such person is charged, shall be admissible at his trial in evidence.

(3) An authorization by the Public Prosecutor or an officer of the Commission of the rank of Commissioner or above as authorized by the Public Prosecutor under subsection (1) may be given either orally or in writing; but if an oral authorization is given, the Public Prosecutor or the officer of the Commission of the rank of Commissioner or above as authorized by the Public Prosecutor shall, as soon as practicable, reduce the authorization into writing.

(4) A certificate by the Public Prosecutor or the officer of the Commission of the rank of Commissioner or above as authorized by the Public Prosecutor stating that the action taken by an officer of the Commission in pursuance of subsection (1) had been authorized by him under that subsection shall be conclusive evidence that it had been so authorized, and such certificate shall be admissible in evidence without proof of signature thereof.

(5) No person shall be under any duty, obligation or liability, or be in any manner compelled, to disclose in any proceedings the procedure, method, manner or means, or any matter related thereto, of anything done under paragraph (1)(a), (b) or (c).

(6) For the purpose of this section, “postal article” has the same meaning as in the Postal Services Act 1991 [Act 465].